Anyone who’s went through a well-thought-out serious dose of mushrooms can tell you that psilocybin is a truly life-changing compound.

This molecule first emerged 10 to 20 million years ago, and its primary function was to repel predators from feasting on the mushrooms.

In the millions of years that followed creatures with superior sentience gradually evolved, and in humans the effects produced by psilocybin are completely different from the original purpose of this molecule.

How come some mushrooms have psilocybin?

Over two hundred species of mushrooms (which grow in almost every corner of the world) have developed psilocybin, and what’s fascinating is that this molecule seems to have evolved “separately” in each of them.

This unusual process where the beneficial genetic material jumps from species to species is called the horizontal gene transfer. This specific type of gene transfer is usually a result of a specific threat or opportunity in the environment.

It is speculated that the psilocybin-carrying genetic material “jumped” from one species to another because a great number of differing mushrooms grow on manure and rotten wood, but more importantly because in this fungi-friendly environment there’s also a lot of insects, who are the mushroom’s natural enemies.

Science has figured out (1) that unlike with humans (whose consciousness distorts in profound ways when psilocybin is introduced), psilocybin causes insects to perceive that they are full, which prevents them from eating the mushroom in question.

This sensation in the insects’ mind makes psilocybin a very sophisticated defense mechanism, because it doesn’t poison or kill them, but instead deters predatory insects from continuing to eat the mushroom.

How does psilocybin induce psychedelic effects?

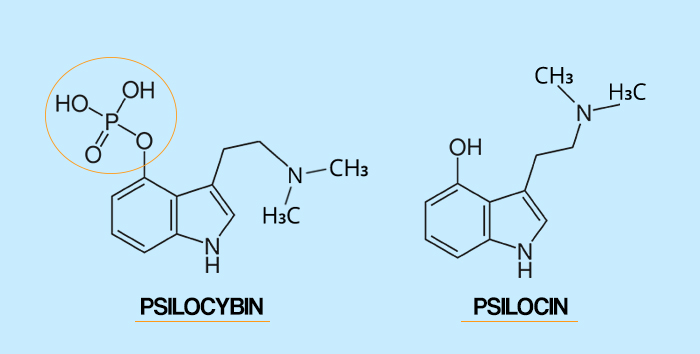

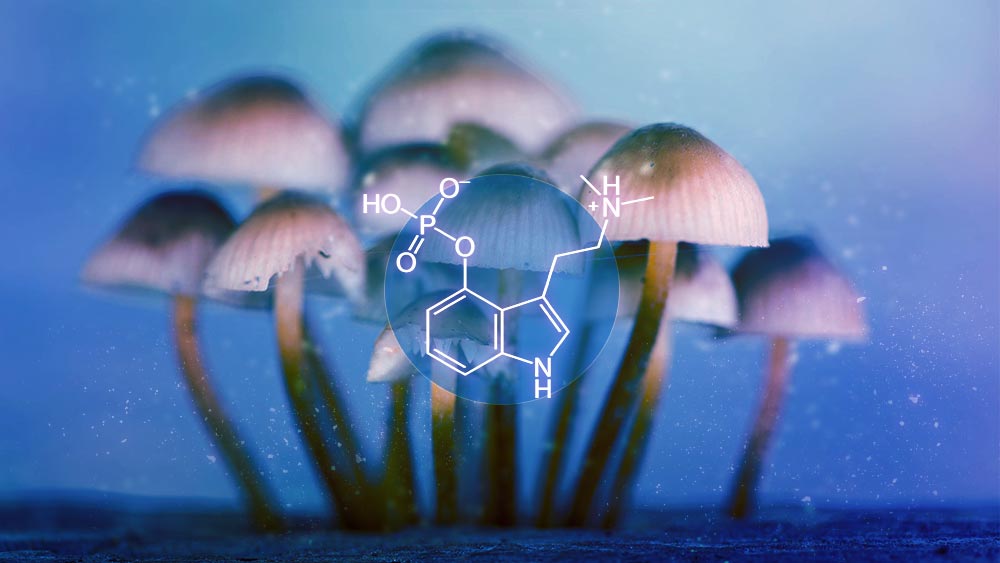

Firstly, when we consume psilocybin mushrooms, the presence of water molecules in the body causes a phosphate group to detach from the psilocybin molecule.

This process is called dephosphorylation, and it converts psilocybin into psilocin, which is responsible for the mind-altering effects.

Once psilocybin is converted to psilocin, this molecule is now able to attach to specific receptors in the brain.

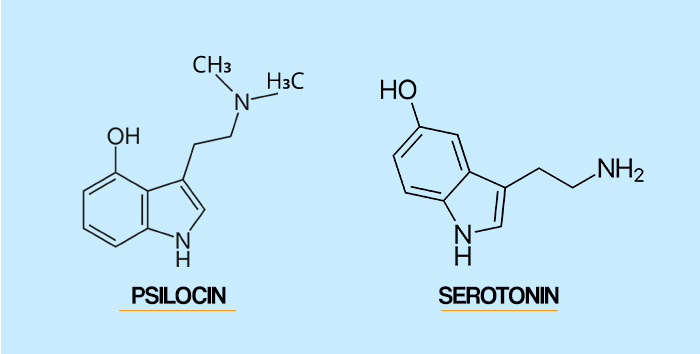

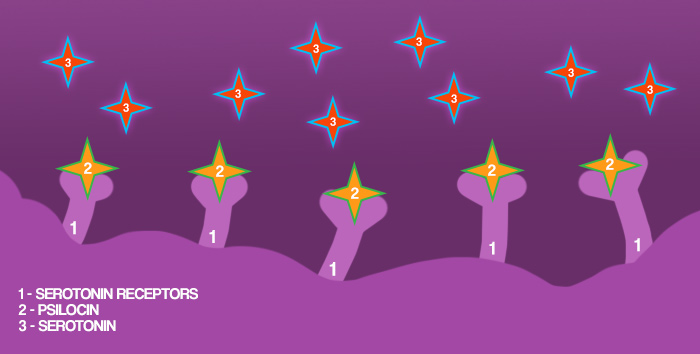

Because it is structurally quite similar to serotonin, psilocin prevents the reuptake (reabsorption) of serotonin on these serotonin receptors sites.

This means that psilocin temporarily “hijacks” serotonin receptors from serotonin, and stimulate them throughout numerous important regions of the brain.

This ability to stimulate serotonin receptors means that psilocin is a serotonin receptor agonist.

Serotonin is an immensely important neurotransmitter, with an extremely wide set of functions within the human body.

It’s frequently called the “happy chemical” as it’s essential for our feelings of wellbeing and happiness, but it is also intricately connected with numerous other functions such as mood, appetite, sleep cycles, sexual desire, memory and learning. Low levels of the serotonin molecule is also tightly tied with depression.

Similar to serotonin, but not the same

Psilocin molecules are capable of stimulating serotonin receptors because they are structurally similar to serotonin, and a very similar thing happens with cannabinoids from cannabis, which are able to stimulate the cellular receptors of the endocannabinoid system.

The endocannabinoid receptors have evolved to be stimulated by our endogenous endocannabinoids like anandamide. But, because cannabinoids like THC and CBD are structurally similar to our body-made endocannabinoids, endocannabinoid receptors also respond to the simulation of cannabinoids.

Just like endocannabinoids and cannabinoids are different, psilocin and serotonin are different. They don’t produce the same effects, even though they are similar in structure and fit onto the same receptors.

Since psilocybin (and subsequently psilocin) still remains a Schedule 1 substance, science is still having a hard time uncovering all of its mysteries, because the illegality cripples both the funding and volume of research.

What we know so far

Research has shown that psilocin stimulates serotonin receptors differently than serotonin, and the main difference is that psilocin activates phospholipase A2 enzymes, unlike serotonin which activates phospholipase C enzymes.

This basically means that psilocin and serotonin produce different effects when they stimulate these receptors, and other psychedelic compounds like DMT and LSD also activate phospholipase A2.

This kind of receptor activation is produces a cascading domino effect, affecting numerous regions in the brain – most importantly the default mode network.

The default mode network

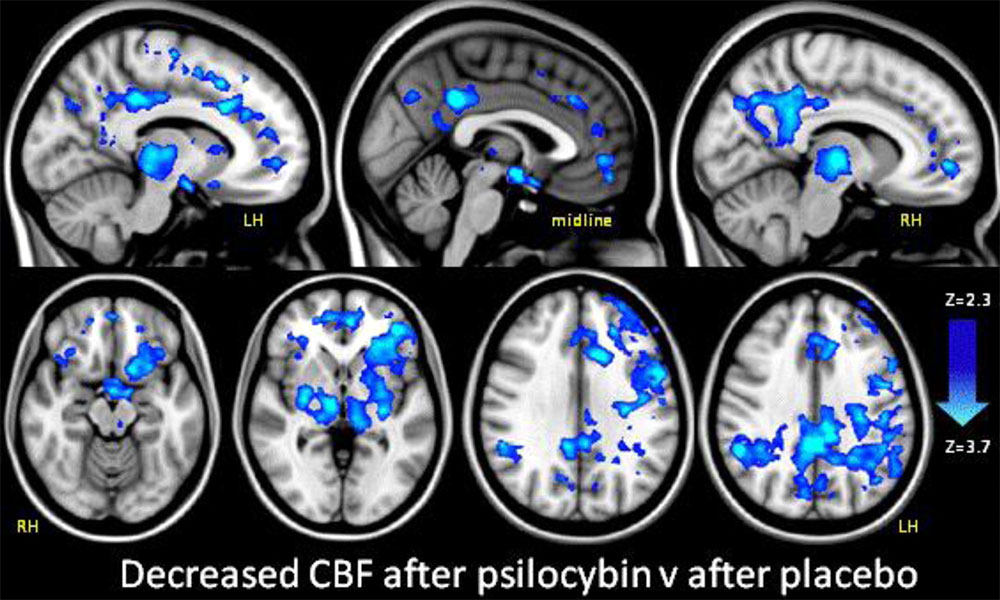

When scientists first began taking brain scans of people under the influence of psilocybin, they expected to see a great increase in brain activity, corresponding with the intense sensations that people regularly report.

But unexpectedly, they saw a significant decrease of cerebral blood flow (CBF) in a specific network that is essential to our perception of self.

The default mode network (DMN) is a set of structures located in the midline of the brain, which connects structures of the frontal cortex (the most recently evolved part, home to our executive functions like planning, reasoning and problem solving), with older and deeper structures of the brain that are involved with emotions and memory.

All of this entails that the DMN is a crucial hub in the brain, involved with self-criticism, self-reflection and negative ruminating thoughts. It is also connected with our ability to think about both the past and the future, which is considered crucial for a well-developed sense of identity.

The DMN also plays a part in the theory of mind, which is the ability of humans to imagine various mental states (desires, intents, emotions and beliefs) in other people.

The ability of this molecule to temporary silence the default mode network is theorized to be responsible for the sensations of ego dissolution that many people experience on psilocybin.

This brief disconnect from the DMN results in a reconnection to everything, and the current research with psilocybin is showing astonishing results for people suffering from depression and addiction, as they are most afflicted with ruminating negative thought-patterns.

While the DMN is shut down, new neural connections are being formed, which brings us to the second important effect of psilocybin.

Novel brain connections

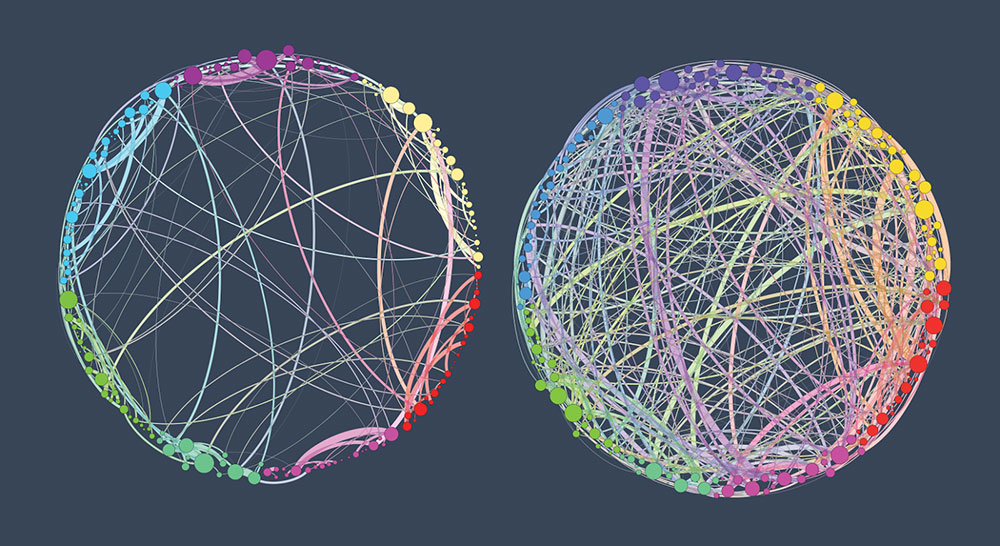

A 2014 study was performing functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) brain scans on 15 participants who all had previous experiences with psychedelics, while they were on psilocybin.

The scans showed a significant decrease in activity in the default mode network, but more importantly, the data showed that the brain under the influence of psilocybin was creating a lot of new biologically stable neural connections.

Because the regular functioning of the default mode network is temporarily inhibited, structures within the brain that otherwise don’t directly communicate are able to connect.

This momentary rearrangement is thought to be responsible for the dramatically positive shifts in perspective that so many people experience with psilocybin, because it allows an otherwise-constricted and loop-driven brain to develop brand new insights and perspectives.

Even though these novel connections are only temporary and the functions of the brain are normalized after the psilocybin session, the study showed that the ego-dissolution in combination with new insights produces positive long-lasting neurological changes.

This occurs because the consciousness has had a chance to “experience” a different and less-constricted form of functioning, and this effect is something that isn’t easily forgotten.

Changes in the visual cortex

One of the most captivating effects of psilocybin are the vivid visual hallucinations, and scientists are currently trying to unravel how they occur.

Even though the 2019 study dealing with this correlation was performed on mice, it provided the research team with a lot of tangible insights.

A compound called DOI (2,5-Dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine) was used in this research, which is just like psilocybin activates phospholipase A2 enzymes.

This type of stimulation of the serotonin receptors caused the visual cortex to behave in a very disorganized fashion.

In normal states, exposure to a visual stimuli would result in an instant burst of neural activity, but for mice on DOI, this initial response was significantly obstructed.

Neurons fired with decreased intensity, and the timing of the firing was atypical. The main hypothesis is that hallucinations occur because the brain is trying to compensate for the lack of data it’s getting from the visual cortex.

The diminished input received from the main visual processing regions is possibly causing the brain to counterbalance the lack of information, which results in strange visual distortions.

This hypothesis coincides with the sensations experienced on a psilocybin trip, because the user is intellectually aware of the experienced hallucinations.

Conclusion

Humans have been utilizing psilocybin mushrooms for spiritual purposes for millenia, but the resurgence of interest within the scientific community for psilocybin is showing that a responsible and educated use of this molecule is extremely beneficial for both our psyche and our spirit.

Contemporary research is currently verifying with factual evidence that psilocybin therapy provides a multitude of benefits for numerous disorders of the mind, including treatment-resistant depression, end-of-life depression and anxiety, and alcohol and nicotine addiction.

Mark Fuller January 1, 2020 at 12:28 am

Very good. Thank you.

Marco Medic January 3, 2020 at 10:15 am

Much obliged Mark.